"We stand in solidarity"-Asian American Artist Confront Racism Favorite

Unleashed by anxiety over the pandemic, the nationwide rise in anti-Asian hate has served as a call to action for many Asian American artists to take a stand: To actively challenge the historic negative stereotype of the vice- and disease-ridden Yellow Peril; to dismantle the pernicious and divisive myth of the model minority that pits achievements by Asian Americas as judgements against other communities of color; and to advocate for social justice, equity, and inclusion for all. Located on opposite coasts, the work of photographer Mike Keo and multimedia artist Monyee Chau exemplify this new generation of Asian American activist-artists who are working within their respective communities to effect change. Both skillfully employ social media to raise awareness.

In late February 2020, weeks before Connecticut declared a state of emergency, Mike Keo started the viral social media campaign #IAmNotAVirus. Unsettled by the xenophobic monikers and politicization of the virus, and outraged by a racial incident targeting a family member, Keo, who is of Khmer descent, began taking portraits of Asian Americans friends and acquaintances and asked each sitter to share three #IAm statements about themselves, their interests, and their passions. By presenting individuals, #IAmNotAVirus humanized those who would be subject to anti-Asian harassment. Following the murder of George Floyd, Keo initiated the social media campaign #IAmNotAThreat in support of Black Lives Matter. As a father of two small children, Keo and a team of likeminded artists developed and distributed over 1,000 copies of a coloring book, Asian American Pioneers, to educate young children on the historical contributions of Asian Americans. Keo is now to working pass SB-678, a bill to include Asian Pacific American studies in public school curriculum across the state of Connecticut.

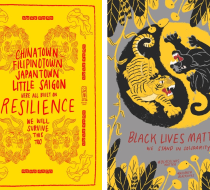

In April 2020, following a disturbing incident when white nationalists vandalized Asian-owned businesses in Seattle’s Chinatown, Monyee Chau—who is of Taiwanese and Chinese descent and queer, and who was born and raised in the neighborhood—created a poster to bolster the spirits of area residents. Four simple line drawings of lion heads frame the inscription: “Chinatown Filipinotown Japantown Little Saigon / were all built on Resilience / We will survive this too.” The poster was wheat-pasted around Seattle and a digital version was projected on High Street in London, England by W1 Curates. Recognizing the current vulnerability of Chinatown residents, Chau also designed a pamphlet resembling a take-out menu titled “Chinatowns in America and The Racism that Built Them” to highlight the historical significance of Chinatowns as safe havens for Asian immigrants, and includes historical facts and a list of resources. The menu was immediately downloaded and shared over 18,000 times. Like Keo, Chau took immediate action in response to the horrific murder of George Floyd, designing another poster with a powerful graphic of a crouching tiger and black panther circumscribed within a yellow and black yin-yang symbol and the inscription “Black Lives Matter: We stand in solidarity.”

Keo and Chau follow a long line of Asian American activist-artists and curators who deserve wider recognition. Most notably, in 1990 artists Ken Chu and Bing Lee and curator Margo Machida founded Godzilla: Asian American Art Network, an influential collective of artists and curators in New York City. Its members included Tomie Arai, Allan deSouza, Karin Higa, Arlan Huang, Byron Kim, Colin Lee, Janet Lin, Mei-Lin Liu, Stephanie Mar, Yong Soon Min, Helen Oji, Paul Pfeiffer, Eugenie Tsai, Lynne Yamamoto, Alice Yang, and Garson Yu, among many others.

Members met regularly at Art in General, an alternative art space on the border of Chinatown, to present and discuss their work. They also published a newsletter and organized exhibitions. In 1991 in an open letter, Godzilla successfully petitioned the Whitney Museum to include more Asians in its exhibitions and staff, resulting in Byron Kim’s participation in the 1993 biennale where he debuted his powerful work Synecdoche (now in the collection of the National Gallery) and the appointment of Eugenie Tsai as a curator and the director of its now closed branch in Stamford, Connecticut in 1994.

Although Godzilla disbanded in 2001, former members continue their individual creative practices and remain politically active. Several recently joined together with other artists to form G19 and in March 2021, in a coordinated response, withdrew en bloc from the comprehensive retrospective exhibition Godzilla vs. The Art World: 1990-2001 that was scheduled to open in May at the Museum of Chinese in America in New York City, in protest over the museum’s support of a new jail in Chinatown and in solidarity with community groups and local residents whose opposition was silenced.

The activism of the historic collective Godzilla, new groups like G19, and the individual work of recently activated artists like Keo and Chau inspire us to find ways to make the arts and our communities more equitable. Thankfully, A/P/A Voices: A COVID-19 Public Memory Project, initiated by the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at New York University in collaboration with artists and scholars Tomie Arai, Lena Sze, Vivian Truong, and Diane Wong, is actively collecting oral histories and artifacts created during this urgent period of reckoning. The materials will be preserved for future study at the NYU Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives. Because May is AAPI (Asian American Pacific Islander) Heritage Month, let us as Asians and as allies celebrate our advancements, mourn setbacks, and prepare for the continued work ahead.