General Idea and the AIDS crises 1 Favorite

The Canadian artist collective General Idea found its drive in the AIDS epidemic, becoming aesthetically and conceptually refined in the in the 1970s and ’80s, after long forays into absurdity and performances evocative of Dada and Fluxus. A retrospective presented by the Jumex Museum elucidates the collective’s progression from troublemakers to activist artists calling attention to the epidemic, which ultimately claimed two of its three members and countless others in the queer creative community.

It’s a rare pleasure to see an artist or group of artists make their strongest work near the end (Cy Twombly’s 2014 retrospective, Paradise, provided an astonishing example). For General Idea — which consisted of AA Bronson (born 1946), Felix Partz (1945–94), and Jorge Zontal (1944–94) — the impending misery of death brought about action rather than despair. The group approached the most serious possible subject matter through contradictory, lighthearted pop. Of course, Bronson went on to solo success, while artists like San Francisco’s Nayland Blake have furthered General Idea’s line of inquiry through performances and large-scale installations that reconstruct queer history as both celebrations and memorials.

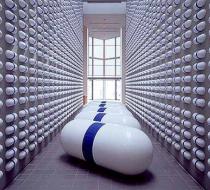

This retrospective, titled Broken Time, is framed by a repeating bas relief motif of giant pills — a visualization of the countless drugs those infected with HIV ingested in hopes of lessening the deadly effects of the illness — and the collective’s most iconic image, a repeated pattern of the “AIDS” acronym modeled after Robert Indiana’s famous “LOVE” prints and sculptures. The evolution that the work takes, chronologically laid out across two floors of the museum, is drastic, beginning with text, video, and performance work derivative of the Fluxus and Dada groups, and ending with tweaked commercial objects pleading the urgency of the AIDS crisis, including a General Idea brand “Jockey Short Shopping Bag” and a series of caricature self-portraits by the three artists.

General Idea wasn’t just pioneering in terms of art confronting the AIDS crisis. The group also forged new ways of making through experimental text, publication, and performance. One of the first vitrines in the exhibition features several dozen performance sketches, including some of the trio’s better known chain letters, each no larger than a note card or sheet of office paper. “For one minute close your eyes and open your ears,” reads one chain letter. “Listen. What do you hear? Make a list and send it to a friend.” Another note card reads, “On waking tell your room what you think of it. Give it a piece of your mind.”

The performance sketches in the vitrine show that the group was steeped in alternative and queer approaches to making during the ’50s and ’60s. The directives for mini performances are also the earliest examples of General Idea’s work that takes place outside of the gallery space and only leaves documentation or description to be appreciated as form. The tiny performances themselves are purposefully formless, usually conceived without any audience in mind. The sketches for artistic actions are personal meditations, affectionate exchanges, and exercises in presence.

Unsurprisingly, some of General Idea’s more absurd and improvisational musings on the nature of performance and art practice were met with eviscerating criticisms or outright incomprehension. “I think it’s a practical joke and a waste of money, and somebody is putting us on,” a representative of the St. Lawrence Centre for the Arts told General Idea in a phone conversation that the artists documented during a presentation of their 1970 performance “What Happened” at the Festival of Underground Theater in Toronto. The multi-part performance, which was based on Gertrude Stein’s play of the same name, was spread across the three week festival and included the “Miss General Idea Pageant.”

Further on in the exhibition, moving into the hippie era — when the members of General Idea were presumably experimenting with the same drugs as so many of their peers — their work began to reflect the psychedelic times. In the pieces from that period, the aesthetics — pyramid forms and neon colors, for example — echo other alternative artist groups and communes, such as Drop City’s Clark Richert. From there, the collective’s work takes on a noticeably more material form, including paintings in which it represented playful, gender-bending sex acted out by neon poodles — a fun foray into free love before the seriousness of AIDS shackled their work to the terminal disease.

It’s encouraging that the Jumex team has gained back some specificity and moved — at least a little bit — away from over hanging its galleries and cluttering the exhibition spaces. The exhibition is still packed to the gills, but for the most part not gratuitously so. That said, one large gallery of Broken Time is completely taken up by an irritating installation that seems intended to protest climate change. Titled “Fin de sciècle” (1990), it consists of a group of toy stuffed seals sitting on a sea of Styrofoam in place of ice — in other words, a crazy waste of space. It would have been a more effective use of space if the giant foam monstrosity was left out and the rest of the work was given some room to breath. As such, it makes for a truly bewildering, off-topic departure from a catalogue of poignant and ephemeral projects activated by tangible action.

-

By Devon Van Houten Maldonado