Swift Project Favorite

"Since the progress of civilization in our country has furnished thousands of convenient places for this Swallow to breed in, safe from storms, snakes, or quadrupeds, it has abandoned, with a judgment worthy of remark, its former abodes in the hollows of trees, and taken possession of the chimneys which emit no smoke in the summer season." John James Audubon, The Chimney Swallow (or American Swift, Chimney Swift, Chaotura Pelasgia), from The Ornithological Biography, 1826.

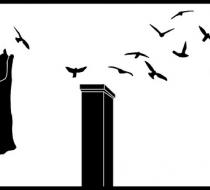

John James Audubon (1785-1851), the great French-American ornithologist and artist, called it a swallow, but it is actually a swift, a different species more closely related to the hummingbird. An indigenous migratory bird of North and South America, the Chimney Swift, as Audubon points out, did take advantage of the rise of chimneys on homes and factories throughout a range that extends up into Southern Ontario and Eastern Canada; but, he was mistaken to refer to this as a "judgment," an intentional, thought-out strategic act. It was luck and chance, mixed with a certain irony, that created the opportunity for a new home for this species. The expanding human presence fuelled by European colonization of the Americas had caused the rapid decline of the bird's natural habitat when lands were cleared. The swifts were lucky that a suitable alternative emerged in its place, offered up, unintentionally, by the very force that consumed the carcasses of old growth timber, which were their preferred sites to roost and nest. Audubon dedicated much space in his writings to an experience observing a colony of over 9000 birds within a single giant dead sycamore near Louisville, Kentucky, the birds entering and exiting from the tree "like bees," their vibrant mass emitting "the sound of a large (mill) wheel revolving under a powerful stream." If you live in a town close to water where the heat of summer breeds fogs of mosquitos, having large flocks of Chaotura Pelasgia moving into your abundant chimneys was (and still is) clearly a very good thing. We got lucky when these birds moved house as it caused a significant rise in the populations of a species that devours bugs on the wing (what ornithologists call avian insectivores). It is unlikely that this history of chance opportunistic adaptation with its interspecies benefits will repeat itself.

Throughout the city of Guelph, the once abundant Chimney Swift is in rapid decline, now rare and listed as "at risk." Habitat transformation is in the works again along with human induced changes to the environment. Many suitable chimneys are being knocked down (no longer needed and often a safety hazard due to their state of decay) or capped (for conservation reasons). The type of open masonry chimneys that so suited the swift, are no longer state of the art and efficient by contemporary standards and are therefore not being replenished. And so the swift finds itself at another crossroads, displaced and homeless. It is a phenomena not unique to Guelph but common throughout the swift's historic range. To be clear, the loss of roosting sites may not, and probably isn't, the only change affecting this fragile species, but it has to be a significant factor. DodoLab wants to know what can be done to assist these feathered friends to adapt to current changes in their environment and, by extension, to explore wider issues about adaptation, change and displacement in the community?

Working with individuals and groups in Guelph, we are developing a combination of design/build strategies and creative interventions to both attempt to address the plight of the Chimney Swift and encourage and nurture dialogue and conversation within the community, to explore how we can help and what we can learn through a community-based and interspecies dialogue. What can the Chimney Swift teach us about being in an unpredictable world in flux, the fragility of our systems of living and the potential endgame of adaptations? Human society tends to believe that we are endlessly inventive and adaptive, a belief which gives us hope for the future and our ability to address both natural and human initiated change. But while we may be unique among species in our ability to actively think ahead, plan and attempt to design adaptations, we can never, in the end, know what the future holds or what impacts and possibilities the choices we make may have. History, and predictive models for the future, illustrate that systems often suddenly collapse, flip, and don't always progress on a slow manageable track. Species evolve and change and, if they're lucky, persist. The dodo adapted over millennia to suit the specific yet always evolving conditions on its home island of Mauritius, but its ability to adapt could not cope with the speed of introduced change over an intense and condensed time frame. Change can be swift (with great speed and velocity), requiring a response that is swift (quick and prompt) and that is equally swift (smart and clever), a very rare and complex sequence of conditions.