Inside the house that Theaster built Favorite

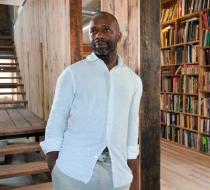

Inside the house that Theaster built

Rising art star and activist Theaster Gates is transforming his neighbourhood, one building at a time

By Helen Stoilas. Features, Issue 238, September 2012

Published online: 06 September 2012

When I arrive at 6901 Dorchester Avenue at nine in the

morning in August, the house is already buzzing with activity—I can hear

the sound of a buzz saw upstairs. The building is due to open later

this month as the Black Cinema House, a space for research into and the

screening of films about African-American culture and by artists of

colour. It is one of the many urban rebuilding projects by the Chicago

artist and current art-world favourite Theaster Gates.

During my visit to his South Side neighbourhood, the

house looked as though it was nearing completion: the first-floor

screening room was mostly finished, with a projector and drop-down

screen already installed next to a gleaming, open kitchen covered in

stainless steel (the ritual of communal meals is an important element of

Gates’s work). The once-abandoned house had been gutted and renovated

to create a warm, inviting space, using materials salvaged from this and

other buildings. The beautiful, darkly stained redwood around the doors

and windows, for example, was rescued from an old water tower, while

the slate green walls in an office turned out to be chalkboards from

Crispus Attucks Elementary School, named after an African-American slave

who was the first casualty of the Revolutionary War.

The Black

Cinema House is just one of the latest rebuilding projects that Gates

has undertaken in Dorchester Avenue and the surrounding neighbourhood of

Grand Crossing. His earlier renovations include a two-storey house that

has been turned into an archive and library, and a former candy store

that served as an event and performance space, and is currently being

re-gutted to take on a new use—perhaps as a further extension of the

archives next door. A few streets away, Gates has bought up a whole

complex of neglected Chicago Housing Authority apartments, which he

plans to turn into mixed-income artist housing with an on-site arts

centre. Last month, the news broke that Gates had rescued a

long-abandoned bank on Stony Island Avenue from demolition by the City,

and he is hoping to transform it into multi-use space to house a

cultural centre, a soul-food restaurant and artist studios. He is due to

present his plan for the bank to the city council this month.

Gates

decides what use a building can take on by looking at what is missing

in the neighbourhood. “Maybe I believe these buildings have higher and

higher uses. Like with a work of art, you never know when it’s really

done until it’s done. You know when it’s not done,” he says. “So I feel

like I’m just trying to connect uses, until the buildings are done. Or

until it feels like this neighbourhood or this place has what it needs

to be really, really healthy.”

Seeing the work done on the

buildings is heartening. It brings a sense of hope to a neighbourhood

hit by poverty, crime and drugs. Driving by the boarded-up windows on

Dorchester Avenue, it is suddenly clear what a sad thing an empty home

is. Tennyson was right when he compared it to a corpse.

Gates’s

work, however, is not just about urban regeneration: it is about

creating a community. One way in which he does this is by using ritual,

often in conjunction with music and food. Gates has a masters degree in

religious studies (along with urban planning and ceramics), and there is

a sense of spirituality running through many of his works. He has a

tendency to slip into a preacher’s booming cadence or hum snatches of

gospel while he’s driving. It’s telling that he has referred to his

renovations as a chance to “redeem” a building or materials. Shared

meals are a regular occurrence at the Dorchester Project, and Gates’s

performances often involve a group of musicians he calls the Black Monks

of Mississippi, who combine gospel and soul music with Buddhist chants.

During a talk at the Armory Show this year, he said performances like

the shared suppers “give me the opportunity to leverage ritual, to ask

hard questions that people don’t normally talk about in Chicago with

people who don’t normally get together. Ritual becomes this tool for

people to feel safe.”

It doesn’t take much to feel comfortable

around Gates, though. He has the ability to adapt his personality to

whomever he’s with. During the morning I spent with him, I saw him be,

in equal turns, meditative, decisive, deeply serious and infectiously

mischievous. While showing a friend his new studio, a former

Anheuser-Busch beer distribution warehouse that he is, of course,

tearing out and rebuilding, he energetically describes his vast

ambitions for the space. While sitting for a quick question-and-answer

session at his kitchen table, he thoughtfully picks over each word. And

when presenting his plans for a $5m renovation of the bank he saved to a

group of preservationists, he gives the facts and figures of the

project with a directness aimed at clearing away any red tape.

In

just two years, Gates’s stock in the art world has risen significantly.

In 2007, he might have complained that he couldn’t find an institution

to show his work, but since his inclusion in the 2010 Whitney Biennial,

the venues have been lining up. Today his schedule is full of art fairs,

biennials, and museum and gallery shows. For Documenta 13, he was

commissioned to renovate and perform in the Huguenot House in Kassel:

this work will form the basis of a solo show at the Museum of

Contemporary Art Chicago next year. This month, for his first show with

London’s White Cube gallery, he is taking over the larger part of its

massive Bermondsey space. This onslaught of attention would be enough to

distract many artists, but although Gates acknowledges the “looming

possibility of insignificance and over-popularisation and decreased

value in the market”, he says he’s not worried about the popularity.

“If

there was any worry, it’s that I would stop feeling purposeful, that

things would no longer matter to me. So what I have to do is keep myself

inspired and really focus on the things that give me purpose.”

He

sees the next few years as a time to complete the projects he’s started

and figure out “what these past couple of years of production really

mean for me”. He says he plans to write and reflect more. “There are

really significant projects that will require a lot of cultivation, and I

want to give myself space to cultivate and just let everything mature.”

The

White Cube show, “My Labour Is My Protest” (7 September-11 November),

will be a chance for Gates to “deepen” some of his ideas about the Civil

Rights Movement and black culture. Some of the earliest work to have

gained widespread critical attention is his series of tapestries and

framed wall boxes made from decommissioned fire hoses, a nod to the

equipment police used to disperse protesters in Alabama. As well as

exploring the question of protest through performance and other work,

including videos and two reclaimed fire engines, the exhibition will

convert the commercial gallery in part into a library to house an

archive of Ebony magazine, recently given to Gates by the Johnson

Publishing Company. “It is a moment to reckon with this body of

knowledge and to think in part about the black American experience and

how that’s had an effect and impact on the world,” Gates says. He also

plans to tackle the assumption that London does not have a race problem,

but rather a class problem.

The show’s title reflects the

personal nature of the works. “The generational dynamics of the impact

of the Civil Rights Movement will be seen through a very nuanced set of

objects that reflect me and my dad,” Gates says. “How did this one

moment make us both feel politically? What are our political realities

and feelings about the value of the Civil Rights Movement?” Gates has

described his father, who worked as a roofer, as a sort of

“anti-activist” who focused more on providing for his family than

protesting. “What became clear is that my dad and I, we labour

differently. Even if we use the same tools… and how he sees the world as

a result of the labour he had to do all his life is very different. But

because of his labour, I don’t have to labour like him; I leverage. And

so labouring and leveraging are big themes in the exhibition. I think

that the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power Movement had

everything to do with how we think differently generationally.”

Working

with a major gallery like White Cube gave him “the freedom and

flexibility to make the show that I wanted to, and I also had the

resources”. Gates adds that “both Jay [Jopling] and Kavi [Gupta] have

been really good about respecting my big ambition”. He has been able to

“deliver a body of work that I wanted… that could seem different from

the culture of the gallery”, but he actually sees some similarities with

other White Cube artists, “like Doris Salcedo and, in a different way,

Antony Gormley—folks who are passionate about making and passionate

about the human experience”.

In addition to the White Cube show,

Gates is planning projects during Frieze Art Fair in London, Expo

Chicago and Art Basel Miami Beach, when he will return to his roots in

ceramic-making with a show at Locust Projects. For this, Gates plans to

collaborate with Japanese potters to turn the space into a production

facility. “Maybe [the objects] won’t actually be things you can use so

much, but it’ll just be the energy and acts of production,” he says.

Unlike

some artists, who might avoid the commercial aspects of the art world,

Gates embraces the whole machine—and, in a way, it helps to drive much

of the work he does. The proceeds from the sale of his art objects

through galleries and at art fairs are siphoned back into his community

building projects. “If we could just stop thinking about the museum as

the legitimising space, and the fair as the delegitimising space,” Gates

says. “They’re really just moments of encounters. And then we can make

decisions about what kind of role we want in those spaces, what kind of

encounters we want to create. Artists should be mindful of what’s at

stake, and why we do this or that.”

Before Gates arrived for our

interview, I spoke to some of the people working on the Black Cinema

House, many of whom are artists and craftsmen themselves. On the ground

floor, John Preus was working on a stairway leading to the educational

rooms in the basement, using wood donated by the ReBuilding Exchange. He

co-founded the nearby Southside Hub of Production in Hyde Park, a

community space that organises classes, cultural events, performances

and exhibitions.

Upstairs, Tadd Cowen, Dave Correa and a young

man called Charles were finishing the apartment that would serve as a

living space for Gates, and later perhaps other artists. Charles, who

comes from the area, is working as an apprentice.

“What this

level of productivity does is create opportunities for other people to

be highly productive and self-employed, and to use the best parts of

their creative selves to partner with me to do bigger things. They don’t

have to wear the brand of ‘Theaster’ or the moniker of ‘participatory,

social, relational’. I think production—industrial production, hand

production, anonymous production, those acts of creation that happen in

that form—are just as important to me,” Gates says.

Preus and

Cowen travelled to Kassel to help work on Gates’s project for Documenta,

12 Ballads for the Huguenot House. When I said that Gates’s current

popularity must keep them all busy, Preus agreed: “We just try to keep

up.”

For more Chicago features, see The Art Newspaper 2, the pull-out section in our new-look September issue (on sale now), or subscribe to our digital edition